Dominique O’Brien—her friends call her Mo—lives a curious double life with her husband, Bob Howard. To the average civilian, they’re boring middle-aged civil servants. But within the labyrinthian secret circles of Her Majesty’s government, they’re operatives working for the nation’s occult security service known as the Laundry, charged with defending Britain against dark supernatural forces threatening humanity.

Mo’s latest assignment is assisting the police in containing an unusual outbreak: ordinary citizens suddenly imbued with extraordinary abilities of the super-powered kind. Unfortunately these people prefer playing super-pranks instead of super-heroics. The Mayor of London being levitated by a dumpy man in Trafalgar Square would normally be a source of shared amusement for Mo and Bob, but they’re currently separated because something’s come between them—something evil.

An antique violin, an Erich Zann original, made of human white bone, was designed to produce music capable of slaughtering demons. Mo is the custodian of this unholy instrument. It invades her dreams and yearns for the blood of her colleagues—and her husband. And despite Mo’s proficiency as a world class violinist, it cannot be controlled…

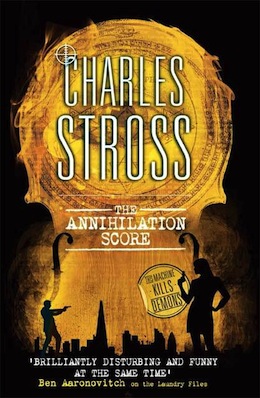

From Hugo Award-winning author Charles Stross comes The Annihilation Score, the next case in The Laundry Files—available July 7th from Penguin Books.

Part One: Origin Story

Prologue: the Incorrigibles

Please allow me to introduce myself…

No. Strike that. Period stop backspace backspace bloody computer no stop that stop listening stop dictating end end oh I give up.

Will you stop doing that?

Starting all over again (typing this time: it’s slower, but dam speech recognition and auto-defect to Heckmondwike):

My husband is sometimes a bit slow on the uptake; you’d think that after ten years together he’d have realized that our relationship consisted of him, me, and a bone-white violin made for a mad scientist by a luthier-turned-necromancer. But no: the third party in our ménage à trois turns out to be a surprise to him after all these years, and he needs more time to think about it.

Bending over backwards to give him the benefit of the doubt, this has only become an issue since my husband acquired the ability to see Lecter—that’s what I call my violin when I argue with him—for what he is. (He. She. It. Whatever.) Bob is very unusual in having lately developed this ability: it marks him as a member of a privileged elite, the select club of occult practitioners who can recognize what they’re in the presence of, and stand fast against it rather than fleeing screaming into the night. Like the Vampire Bitch from Human Resources, and what was she doing in the living room at five o’clock in the morning—?

Issues. Vampires, violins, and marital miscommunications. I’m going off-topic again, aren’t I? Time out for tea!

Take three.

Hello.

My name is Mo; that’s short for Dominique O’Brien. I’m 43 years old, married to a man who calls himself Bob Howard, aged 38 and a quarter. We are currently separated while we try to sort things out—things including, but not limited to: my relationship with my violin, his relationship with the Vampire Bitch from Human Resources, and the End Of The World As We Know It (which is an ongoing work-related headache).

This is my introduction to my work journal during OPERATION INCORRIGIBLE, and the period immediately before and after it. We’re supposed to keep these journals in order to facilitate institutional knowledge retention in event of our death in the line of duty. And if you are reading it, you are probably a new Laundry recruit and I am probably not on hand to brief you in person because I’m dead.

Now, you might be wondering why this journal is so large. I could soft-soap you and claim that I just wanted to leave you with a full and balanced perspective on the events surrounding OPERATION INCORRIGIBLE—it’s certainly a valid half-truth—but the real reason is that I’ve been under a lot of stress lately. Nervous breakdowns are a luxury item that we don’t have time for right now, and anyway, all our security-cleared therapists are booked up eight months in advance: so the only psychotherapy I’m getting is the DIY kind, and pouring it all out into a private diary that’s going to be classified up to its armpits and buried in a TOP SECRET vault guarded by security zombies until I’m too dead to be embarrassed by it seemed like a good compromise. So I wrote it this way, and I don’t have the time (or inclination, frankly) to go back and take all the personal stuff out: duty calls, etcetera, and you’ll just have to suck it up.

If I were Bob this journal would probably claim to be written by “Sabine Braveheart” or some such nonsense, but after OPERATION INCORRIGIBLE my patience with silly pseudonyms is at an all-time low. So I’ll use pseudonyms where necessary to protect high-clearance covert assets, and for people who insist on hiding under rocks—yes Bob, if you’re reading this I’m talking about you—but the rest of the time I’ll call a spade a bloody shovel, not EARTHMOVER CRIMSON VORTEX.

Anyway, you got this far so let me finish the prelude to the intro by adding that if you can get past all the Bridget Jones meets The Apocalypse stuff you might pick up some useful workplace tips. (To say nothing of the juicy office gossip.)

Now, to the subject matter in hand (feel free to skip the rest of this foreword if you already know it all):

Bob and I are operatives working for an obscure department of the British civil service, known to its inmates—of whom you are now one—as the Laundry. We’re based in London. To family and friends, we’re civil servants; Bob works in IT, while I have a part-time consultancy post and also teach theory and philosophy of music at Birkbeck College. In actual fact, Bob is a computational demonologist turned necromancer; and I am a combat epistemologist. (It’s my job to study hostile philosophies, and disrupt them. Don’t ask; it’ll all become clear later.)

I also play the violin.

A brief recap: magic is the name given to the practice of manipulating the ultrastructure of reality by carrying out mathematical operations. We live in a multiverse, and certain operators trigger echoes in the Platonic realm of mathematical truth, echoes which can be amplified and fed back into our (and other) realities. Computers, being machines for executing mathematical operations at very high speed, are useful to us as occult engines. Likewise, some of us have the ability to carry out magical operations in our own heads, albeit at terrible cost.

Magic used to be rare and difficult and unsystematized. It became rather more common and easy and formal after Alan Turing put it on a sound theoretical footing at Bletchley Park during the war: for which sin, our predecessors had him bumped off during the 1950s. It was an act of epic stupidity; these days people who rediscover the core theorems are recruited and put to use by the organization.

Unfortunately, computers are everywhere these days—and so are hackers, to such an extent that we have a serious human resources problem, as in: too many people to keep track of. Worse: there are not only too many computers, but too many brains. The effect of all this thinking on the structure of spacetime is damaging—the more magic there is, the easier magic becomes, and the risk we run is that the increasing rate of thaum flux over time tends to infinity and we hit the magical singularity and ordinary people acquire godlike powers as spacetime breaks down, and then the ancient nightmares known as the Elder Gods come out to play. We in the Laundry refer to this apocalyptic situation as CASE NIGHTMARE GREEN, and it is the most immediate of the CASE NIGHTMARE RAINBOW scenarios—existential threats to the future survival of the human species. The bad news is, due to the population crisis we’ve been in the early stages of CASE NIGHTMARE GREEN for the past few years, and we are unlikely to be safe again before the middle of the 22nd century.

And so it is that Bob and I live a curious double life—as boring middle-aged civil servants on the one hand, and as the nation’s occult security service on the other.

Which brings me to the subject of OPERATION INCORRIGIBLE.

I’m supposed to give you a full and frank account of OPERATION INCORRIGIBLE. The trouble is, my experience of it was colored by certain events of a personal nature and although I recognize that it’s highly unprofessional to bring one’s private life into the office, not to mention potentially offensive and a violation of HR guidelines on respect for diversity and sexual misconduct, I can’t let it pass.

Bluntly: Bob started it, and I really can’t see any way to explain what went wrong with OPERATION INCORRIGIBLE without reference to the Vampire Bitch from HR, not to mention Her With The Gills. Or the Mayor, the nude sculpture on the Fourth Plinth, and how I blew my cover. Also: the plague of superheroes, what it’s like to have to set up a government agency from scratch during a crisis, and the truth about what it was like to be a member of the official Home Office superhero team. And finally, the truth about my relationship with Officer Friendly.

So, Bob—Bob? I know you’re reading this—you’d better tell HR to get on the phone to RELATE and find us a marriage guidance counselor with a security clearance.

Because this is what happened, really and truly.

Morning After

Business trips: I hate them.

Actually, hatred is too mild an emotion to encapsulate how I feel about my usual run-of-the-mill off-site work-related travel. Fear and loathing comes closer; I only ever get sent places when things have gotten so out of control that they need a trouble-shooter. Or trouble-violinist. My typical business trips are traumatic and horrible and leave me with nightmares and a tendency to startle at loud noises for weeks afterwards, not to mention an aversion to newspapers and TV reports on horrible incidents in far-off places. Bob is used to this. He does a wonderful job of keeping the home fires burning, providing warm cocoa and iced Scotch on demand, and over the years he’s even learned to pretend to listen. (He’s not very good at it, mind, but the gesture counts. And, to be fair, he has his own demons to wrestle with.)

But anyway: not long ago, for the first time in at least two years, I got sent on a job that didn’t require me to confront oh God, please make them stop eating the babies’ faces but instead required me to attend committee meetings in nice offices, and even a couple of diplomatic receptions. So I went shopping for a little black dress and matching shoes and accessories. Then I splashed out on a new suit I could also use for work after I got back. And then I got to do the whole cocktail-hour-at-the-embassy thing for real.

Cocktail-hour-at-the-embassy consisted of lots of charming men and women in suits and LBDs drinking Buck’s Fizz and being friendly to one another, and so what if half of them had gill slits and dorsal fins under the tailoring, and the embassy smelled of seaweed because it was on an officially derelict oil rig in the middle of the North Sea, and the Other Side had the technical capability to exterminate every human being within two hundred kilometers of a coastline if they think we’ve violated the Benthic Treaty? It was fun. It was an officially sanctioned party. I was not there because my employers thought someone or something vile might need killing: I was there to add a discreet hint of muscle under the satin frock at a diplomatic reception in honor of the renewal of the non-aggression treaty between Her Majesty’s Government and Our Friends The Deep Ones (also known as BLUE HADES).

Cocktail-hour-at-the-embassy consisted of lots of charming men and women in suits and LBDs drinking Buck’s Fizz and being friendly to one another, and so what if half of them had gill slits and dorsal fins under the tailoring, and the embassy smelled of seaweed because it was on an officially derelict oil rig in the middle of the North Sea, and the Other Side had the technical capability to exterminate every human being within two hundred kilometers of a coastline if they think we’ve violated the Benthic Treaty? It was fun. It was an officially sanctioned party. I was not there because my employers thought someone or something vile might need killing: I was there to add a discreet hint of muscle under the satin frock at a diplomatic reception in honor of the renewal of the non-aggression treaty between Her Majesty’s Government and Our Friends The Deep Ones (also known as BLUE HADES).

The accommodation deck was a little utilitarian of course, even though they’d refitted it to make the Foreign Office Xenobiology staffers feel a bit more at home. And there was a baby grand piano in the hospitality suite, although nobody was playing it (which was a good thing because it meant nobody asked me if I’d like to accompany the pianist on violin, so I didn’t have to explain that Lecter was indisposed because he was sleeping off a heavy blood meal in the locker under my bed).

In fact, now that I think about it, the entire week on the rig was almost entirely news-free and music-free.

And I didn’t have any nightmares.

I’m still a bit worried about just why I got this plum of a job at such short notice, mind you. Gerry said he needed me to stand in for Julie Warren, who has somehow contracted pneumonia and is hors de combat thereby. But with 20/20 hindsight, my nasty suspicious mind suggests that maybe Strings Were Pulled. The charitable interpretation is that someone in HR noticed that I was a little overwrought—Bob left them in no doubt about that after the Iranian business, bless his little drama-bunny socks—but the uncharitable interpretation… well, I’ll get to that in a bit. Let’s just say that if I’d known I was going to run into Ramona I might have had second thoughts about coming.

So, let’s zoom in on the action, shall we?

It was Wednesday evening. We flew out to the embassy on Tuesday, and spent the following day sitting around tables in break-out groups discussing fisheries quotas, responsibility for mitigating leaks from deep-sea oil drilling sites, leasing terms for right-of-way for suboceanic cables, and liaison protocols for resolving disputes over inadvertent territorial incursions by ignorant TV production crews in midget submarines—I’m not making that bit up, you wouldn’t believe how close James Cameron came to provoking World War Three. We were due to spend Thursday in more sessions and present our consensus reports on ongoing future negotiations to the ambassadors on Friday morning, before the ministers flew in to shake flippers and sign steles on the current renewal round. But on Wednesday we wrapped up at five. Our schedule gave us a couple hours to decompress and freshen up, and then there was to be a cocktail reception hosted by His Scaliness, the Ambassador to the United Kingdom from BLUE HADES.

These negotiations weren’t just a UK/BH affair; the UK was leading an EU delegation, so we had a sprinkling of diplomats from just about everywhere west of the Urals. (Except Switzerland, of course.) It was really a professional mixer, a meet-and-greet for the two sides. And that’s what I was there for.

I’m not really a diplomat, except in the sense of the term understood by General von Clausewitz. I don’t really know anything about fisheries quotas or liaison protocols. What I was there to do was show off my pretty face in a nice frock under the nose of the BLUE HADES cultural attaché, who would then recognize me and understand the significance of External Assets detaching me from my regular circuit of fuck I didn’t know they exploded like water balloons is that green stuff blood to attend a polite soirée.

But drinking dilute bubbly and partying, for middle-aged values of partying (as Bob would put it), is a pleasant change of pace: I could get used to it. So picture me standing by the piano with a tall drink, listening to a really rather charming Deputy Chief Constable (on detached duty with the fisheries folks, out of uniform) spin sardonic stories about the problems he’s having telling honest trawlermen from Russian smugglers and Portuguese fisheries pirates, when I suddenly realize I’m enjoying myself, if you ignore the spot on the back of my right ankle where my shoe is rubbing—picture me totally relaxed, in the moment right before reality sandbags me.

“Mo?” I hear, in a musical, almost liquid mezzo-soprano, rising on a note of excitement: “Is that really you?”

I begin to turn because something about the voice is tantalizingly familiar if unwelcome, and I manage to fix my face in a welcoming smile just in time because the speaker is familiar. “Ramona?” It’s been seven years. I keep smiling. “Long time no see!” At this moment I’d be happier if it was fourteen years. Or twenty-one.

“Mo, it is you! You look wonderful,” she enthuses.

“Hey, you’re looking good yourself,” I respond on autopilot while I try to get my pulse back under control. And it’s true, because she is looking splendid. She’s wearing a backless, gold lamé fishtail number that clings in all the right places to emphasize her supermodel-grade bone structure and make me feel under-dressed and dowdy. That she’s got ten years on me doesn’t hurt either. Eyes of blue, lips with just the right amount of femme fatale gloss, hair in an elaborate chignon: she’s trying for the mermaid look, I see. How appropriate. There’s just a hint of gray to her skin, and—of course—the sharklike gill slits betwixt collar bones and throat, to give away the fact that it’s not just a fashion statement. That, and the sky-high thaum field she’s giving off: she’s working a class four glamour, or I’ll eat my corsage. “I heard you were transitioning?”

She waves it off with a swish of a white kidskin opera glove. “We have ways of arresting or delaying the change. I can still function up here for a while. But within another two years I’ll need a walker or a wheelchair all the time, and I can’t pass in public anymore.” Her eyebrows furrow minutely, telegraphing irritation. I peer at her. (Are those tiny translucent scales?) “So I decided to take this opportunity for a last visit.” She takes a tiny step, swaying side-to-side as if she’s wearing seven-inch stilettos: but of course she isn’t, and where the train of her dress pools on the floor it conceals something other than feet. “How have you been? I haven’t heard anything from you or Bob for ages.”

For a brief moment she looks wistful, fey, and just very slightly vulnerable. I remind myself that I’ve got nothing against her: really, my instinctive aversion is just a side effect of the overwhelming intimidatory power of her glamour, which in turn is a cosmetic rendered necessary by her unfortunate medical condition. To find yourself trapped in a body with the wrong gender must be hard to bear: How much harsher to discover, aged thirty, that you’re the wrong species?

“Life goes on,” I say, with a light shrug. I glance at Mr. Fisheries Policeman to invite him to stick around, but he nods affably and slithers away in search of canapés and a refill for his glass of bubbly. “In the past month Bob has acquired a cat, a promotion, and a committee.” (A committee where he’s being run ragged by the Vampire Bitch from Human Resources, a long-ago girlfriend-from-hell who has returned from the dead seemingly for the sole purpose of making his life miserable.) “As for me, I’m enjoying myself here. Slumming it among the upper classes.” I catch myself babbling and throw on the brakes. “Taking life easy.”

“I hear things,” Ramona says sympathetically. “The joint defense coordination committee passes stuff on. I have a—what passes for a—desk. It’d all be very familiar to you, I think, once you got used to my people. They’re very—” She pauses. “I was going to say human, but that’s not exactly the right word, is it? They’re very personable. Cold-blooded and benthic, but they metabolize oxygen and generate memoranda all the same, just like any other bureaucratic life form. After a while you stop noticing the scales and tentacles and just relate to them as folks. But anyway: we hear things. About the Sleeper in the Pyramid, and the Ancient of Days, and the game of nightmares in Highgate Cemetery. And you have my deepest sympathy, for what it’s worth. Prost.” She raises her champagne flute in salute.

“Cheers.” I take a sip of Buck’s Fizz and focus on not displaying my ignorance. I am aware of the Sleeper and the Ancient, but… “Highgate Cemetery”?

“Oops.” Fingers pressed to lips, her perfectly penciled eyebrows describe an arch: “Pretend you didn’t hear that? Your people have it in hand, I’m sure you’ll be briefed on it in due course.” Well, perhaps I will be: but my skin is crawling. Ramona knows too much for my peace of mind, and she’s too professional for this to be an accidental disclosure: she’s letting it all hang out on purpose. Why? “Listen, you really ought to come and visit some time. My ma—people—are open to proposals for collaboration, you know. ‘The time is right,’ so to speak. For collaboration. With humans, or at least their agencies.”

The thing about Ramona is, she’s a professional in the same line of work as me and thee. She’s an old hand: formerly an OCCINT asset enchained by the Black Chamber, now cut loose and reunited with the distaff side of her family tree—the inhuman one. She is proven by her presence here this evening to be a player in the game of spies, squishy-versus-scaly subplot, sufficiently trusted by BLUE HADES that they’re willing to parade her around in public. She must have given them extraordinarily good reasons to trust her, such excellent reasons that I am now beginning to think tactically that un-inviting her to my wedding all those years ago was a strategic mistake. Time to rebuild damaged bridges, I think.

“Yes, we really ought to do lunch some time soon,” I say. “We could talk about, oh, joint fisheries policy or something.”

“Yes, that. Or maybe cabbages and kings, and why there are so many superheroes in the news this week?”

“Movies?” My turn to raise an eyebrow: “I know they were all the rage in Hollywood—”

She frowns, and I suddenly realize I’ve missed an important cue. “Don’t be obtuse, Mo.” She takes another carefully measured sip of champagne: I have to admire her control, even if I don’t much like being around her because of what her presence reminds me of. “Three new outbreaks last week: one in London, one in Manchester, and one in Merthyr Tydfil. That last one would be Cap’n Coal, who, let me see, ‘wears a hard-hat and tunnels underground to pop up under the feet of dog-walkers who let their pooches foul the pavement.’” She smacks her lips with fishy amusement. “And then there was the bonded warehouse robbery at Heathrow that was stopped by Officer Friendly.” I blink, taken aback.

“I haven’t been following the news,” I admit: “I spent the past few weeks getting over jet lag.” Jet lag is a euphemism, like an actor’s resting between theatrical engagements.

“Was that your business trip to Vakilabad?”

Her eyes widen as I grab her wrist. “Stop. Right now.” Her pupils are not circular; they’re vertical figure-eights, an infinity symbol stood on end. I feel as if I’m falling into them, and the ward on my discreet silver necklace flares hot. My grip tightens.

“I’m sorry, Mo,” she says, quite sincerely, the ward cooling. She looks shaken. Maybe she got a bit of a soul-gaze in before my firewall kicked her out of my head.

“Where did you hear about Vakilabad?” I need to know: there’s talking shop at a reception, and then there’s this, this brazen—

“Weekly briefing report from Callista Soames in External Liaison,” she says quietly. “I’m the equivalent, um, desk officer, for Downstairs. We share, too.”

“Sharing.” I lick my suddenly dry lips and raise my glass: “Here’s to sharing.” I do not, you will note, propose a toast to over-sharing. Or choose to share with her the details of the Vakilabad job, requested by the Iranian occult intelligence people, or the week-long sleeping-pills-and-whisky aftermath it hit me with because bodies floating in the air, nooses dangling limply between their necks and the beam of the gallows, glowing eyes casting emerald shadows as dead throats chanted paeans of praise to an unborn nightmare—I shudder and accidentally knock back half my glass in a single gulp.

“Are you all right?” she asks, allowing her perfect forehead to wrinkle very slightly in a show of concern.

“Of course I’m not all right,” I grump. There’s no point denying what she can see for herself. “Having a bit of a low-grade crisis, actually, hence someone penciling me in for the cocktail circuit by way of a change of pace.”

“Trouble at home?” She gives me her best sympathetic look, and I stifle the urge to swear and dump the dregs of my glass over her perfect décolletage.

“None. Of. Your. Business,” I say through gritted teeth.

“I’m sorry.” She looks genuinely chastened. Worse, my ward tells me that she is genuinely sorry. It can detect intentional lies as well as actual threats, and it’s been inert throughout our conversation. I feel as if I’ve just kicked a puppy. All right: an extremely fishy benthic puppy who did not have sex with my husband seven years ago when they were destiny-entangled and sent on an insane mission to the Caribbean to smoke out a mad billionaire who was trying to take over the world on behalf of his fluffy white cat. “It’s just, he was so happy to be with you, you know?”

“We are so not going to fail the Bechdel test in public at a diplomatic reception, dear,” I tell her. “That would be embarrassing.” I take her elbow: “I think both our glasses are defective. Must be leaking, or their contents are evaporating or something.” She lets me steer her towards one of the ubiquitous silent waiters, who tops us off. Her gait is unsteady, mincing. Almost as if she’s hobbled, or her legs are partially fused all the way down to her ankles. She’s transitioning, slowly, into the obligate aquatic stage of her kind’s life-cycle. I feel a pang of misplaced pity for her: needing an ever-increasingly more powerful glamour to pass for human, losing the ability to walk, internal organs rearranging themselves into new and unfamiliar structures. Why did I feel threatened by her? Oh yes, that. Spending a week destiny-entangled with someone—in and out of their head telepathically, among other things—is supposed to be like spending a year married to them. And Ramona was thoroughly entangled with Bob for a while. But that was most of a decade ago, and people change, and it’s all water that flowed under the bridge before I married him, and I don’t like to think of myself as an obsessive/intransigent bitch, and Mermaid Ramona probably isn’t even anatomically stop thinking about that compatible anymore. “Let’s go and find a tub you can curl up in while we swap war stories.”

“Yes, let’s,” she agrees, and leans on my arm for balance. “You can tell me all about the bright lights in the big city—I haven’t been further inland than Aberdeen harbor in years—and I can fill you in on what the fishwraps have been pushing. The vigilantes would be funny if they weren’t so sad…”

The accommodation on this former oil rig has, as I’ve mentioned, been heavily tailored towards its new function. Ramona and I make our way out through a couple of utilitarian-looking steel bulkhead doors, onto the walkway that surrounds the upper level of the reception area like a horseshoe-shaped verandah. The ubiquitous “they” have drilled holes in the deck and installed generously proportioned whirlpool spa tubs, with adjacent dry seating and poolside tables for those of us with an aversion to horrifying dry cleaning bills. And there’s a transparent perspex screen to protect us from the worst of the wind.

I help Ramona into one of the tubs—her dress is, unsurprisingly, water-resistant—then collapse upon a strategically positioned chaise alongside. It’s a near-cloudless spring evening on the North Sea and we’re fifty meters above the wave crests: the view of the sunset is amazing, astonishing, adjectivally exhausting. I run out of superlatives halfway through my second glass. Ramona, it turns out, is a well-informed meteorology nerd. She points out cloud structures to me and explains about the North Atlantic thermohaline circulation and frontal weather systems. We get quietly, pleasantly drunk together, and by the end of the third drink a number of hatchets have been picked up, collaboratively discussed, and permanently re-interred in lead-lined coffins. It’s easy to forget that I’ve harbored an unacknowledged grudge against her for years: harder still to remember how long it’s been since I last had any kind of heart-to-heart with a girlfriend who understands what it is that I do.

Unfortunately I now need to curtail this account of our discussion because, drunk or not, diplomatic or not, some of the subjects we touched on are so far above your pay grade that it isn’t funny. However, I think it is safe to say that BLUE HADES are concerned about CASE NIGHTMARE GREEN and are positioning their human-compatible assets—including Ramona—to keep a closer eye on our activities. They are (whisper this) actively cooperating, and you may see more joint liaison committees meeting in the next year than in the previous six decades combined. So it would behoove you to pay attention to whatever you’re told in diversity awareness training courses about dealing with folks with gray, scaly skin and an affinity for outfits featuring high, opaque necklines. Beyond that, however, my lips are sealed.

I’m in my narrow oil rigger’s bunk bed by midnight, lights out and head spinning pleasantly from the fizz and the craic. For the first time in weeks I am relaxed. There is congenial company, a job to do which involves nothing more onerous than staying awake during committee meetings, sedate middle-aged partying in the evenings, and zero possibility whatsoever that I will be hauled out of bed by a dead-of-night phone call in order to go and fight nightmares. What more can a girl ask for?

(Well, the bed could be wider for one thing, and half-occupied by a sleeping husband for another. That would be an improvement, as long as he isn’t stressing out about committee meetings and co-workers and things that go bump in the night. (We both do it, and sometimes we actually make each other worse.) But anyway: that’s a trade-off—blessed peace and anxiety-free quiet against the security blanket effect of being able to reach out in the night and connect. And right now, peace and quiet is winning by a hair’s breadth.)

Lecter is tucked away in his case, which in turn is locked inside the not-insubstantial gun cabinet that I found in my room when I arrived. I can feel his dreams, tickling at the back of my head: disturbing but muted echoes of Vakilabad. I feel slightly guilty that I haven’t taken him out for practice in—is it really two days? Two days without tuning up? It seems like an eternity. But he’s quiescent right now, even glutted, as if in a food coma. That’s good. It means I can ignore his hunger for a while.

So I doze off to sleep. And I dream.

Did you know that keeping a work journal like this—only to be read after one’s demise—can be therapeutic?

Let me tell you about my fucking dreams.

Lecter talks to me in my dreams. Like this one:

I’m dancing and it’s black and white and it’s a waltz, the last waltz at the Vienna Opera Ball—spot the stack of clichés, my internal critic snarks. My partner and I have the floor to ourselves, and we are lit by a lighting rig infinitely high above us that casts a spot as pitiless and harsh as the supernova glare of a dying star. My partner is a full head taller than me, so I’m eye-to-eye with the ivory knot of his tie—yes, white tie and tails, very 1890s. I’m wearing an elaborate gown that probably came out of a glass cabinet at the V&A, fit for a long-dead Arch-Duke’s mistress. I can’t see his face and he’s clearly not Bob (Bob has two left feet) for he leads me in graceful loops, holding me in a grip as strong as spring steel. I let him lead, feeling passive, head whirling (or is that the Buck’s Fizz I put away earlier?), positively recumbent as he glides around the floor. It’s a two-step in 3/4 time, rather old-fashioned and easy enough to keep up with, but I can’t place the composition: it reminds me of von Weber, only… not. As we twirl briefly close to the edge of the stage I glance into the umbral shadows of the orchestra pit, past my partner’s occlusive shoulder. There are gaps in the orchestra, like teeth missing from a skull. A faint aroma of musty compost, overlaid with a graveyard tang. The musicians are dead and largely decomposed, swaying in the grip of their instruments, retaining only such body parts as the performance requires. The lead violin’s seat gapes empty.

***We haven’t played today,*** Lecter whispers inside my head.

“I know.” I lean my chin against his shoulder as he holds me tight, spinning before the empty eye sockets of the bone orchestra. It’s easy to melt into his grip: he’s a wonderful dancer and his iron embrace locks me in like my antique gown’s stays.

***You shall join the orchestra eventually. It’s your destiny.*** He means the orchestra of his victims, the musicians he has twisted and killed over the decades since his grisly genesis in Erich Zahn’s workshop in 1931. He was created at the behest of one Professor Doktor Mabuse. Mabuse the Gambler was a monster, and Zahn his enabler—but Lecter has outlasted and surpassed both of them.

“Not this time.” I spare another glance for the shades beyond the stage. We have, it seems, an audience consisting only of the dead and drained. I squint: I have a feeling I should recognize some of them.

***No, my dear. This is not your destination; this is merely the vestibule.***

My dance partner pulls me into a slightly tighter embrace. I lean against him and he breaks with the dance, lowering his grip to my waist, lifting me from the floor to whirl around in helpless orbit.

“What are you doing?” I cling to him for dear life. He’s overpowering and gorgeous, and despite the charnel horrors around us I find him exciting and exhilarating. Blood is pounding in my ears, and I flush, wanting him—this is silly—as if he’s a human lover. Which is crazy talk and unimaginably dangerous and anyway I’m married, but faceless strong stranger whirling me away in a romantic whirlwind race to nowhere is an incredibly strong cultural trope to deconstruct when you’re so turned-on you’re desperately trying not to hump his leg and get a grip on yourself Mo, this is not good—

“Get the fuck out of my head,” I snarl, and awaken to find myself lying stone-cold sober in a tangle of sheets saturated with ice-cold sweat, my crotch hot and throbbing, while the cobwebby echoes of Lecter’s dream lover giggle and chitter and bounce around the corners of my skull like so many Hallowe’en bat-toys.

***Bitch,*** Lecter mocks. ***You know you want me.***

“Fuck you.”

***Touch me, sex me, feed me.***

“Fuck you.”

I’m on my feet, fumbling with the key to the gun locker. It contains no guns: just a scuffed white violin case that sports a dog-eared sticker reading THIS MACHINE KILLS DEMONS. Other, more subtle wards engraved between the laminated layers of the case bind the contents in an approximation of safety, much like the sarcophagus around the Number Two reactor at Chernobyl; the instrument itself is considerably deadlier than an assault rifle. I lean against the wall as I lift the case out and lay it on the damp bed-sheets, then flick the clasps and lift the coffin-like lid.

Lecter gleams within, old bone in the moonlight shining through the cabin’s porthole. I touch his neck and draw my fingers slowly down it, across his body towards the saddle. (Is it my imagination, or does his fingerboard shudder in anticipation?) I reach into the lid with my other hand and pick up the bow. A brief measure from the Diabelli Variations, perhaps? What could be the harm (other than the risk of disturbing my neighbors, who in any case are sleeping in the accommodation deck of a former oil rig, which was presumably designed with sound-proofing in mind)?

I wrap my hand around his bridge and lift him gently, then raise his rigid body to my shoulder and rest my cheek against his rest. For an instant I have a disturbing hallucination, that I’m holding something that doesn’t resemble a violin so much as an unearthly bone-scaled lizard, f-hole shaped fistulae in its shell flashing me a glimpse of pulsing coils of blood-engorged viscera within—but it passes, and he is once again my instrument, almost an extension of my fingertips. I purse my lips and focus, lower the bow to touch his strings as delicately as don’t think of that, begin to draw it back and feel for his pitch—

Then my phone rings.

***Play me!*** Lecter snarls, but the moment has passed.

My phone shrills again as I lower bow and body to the bed and rummage under my discarded dress for the evening clutch. I get to the phone by the fourth ring, and answer it. It’s a blocked number, but that doesn’t mean anything. “Mo speaking. Who is it?”

“Duty Officer, Agent Candid. Please confirm your ID?” He gives me a password and I respond. Then: “We have a Code Red, repeat, a Code Red, Code Red at Dansey House. The Major Incident Contingency Plan has been activated. You are on the B-list; a Coast Guard helicopter is on its way out from Stornoway and will transport you directly to London. Your fallback coordinator is Vikram Choudhury, secondary supervisor is Colonel Lockhart. Report to them upon your arrival. Over and out.”

I drop the phone and stare at Lecter. “You knew about this, didn’t you?”

But the violin remains stubbornly silent. And when I re-inter him in his velvet-lined coffin, he seems to throb with sullen, frustrated desire.

I don’t like helicopters.

They are incredibly noisy, vibrate like a badly balanced tumble drier, and smell faintly of cat-piss. (Actually, that latter is probably a function of my sense of smell being a little off—jet fuel smells odd to me—but even so, knowing what it is doesn’t help when you’re locked in one for the best part of four hours.) The worst thing about them, though, is that they don’t make sense. They hang from the sky by invisible hooks, and as if that’s not bad enough, when you look at a diagram of how they’re supposed to work it turns out that the food processor up top is connected to the people shaker underneath using a component called the Jesus Nut. It’s called that because, if it breaks, that’s your last word. Bob rabbits on about single points of failure and coffin corners and what-not, but for me the most undesirable aspect of helicopters can be encapsulated by their dependence on messiah testicles.

This particular chopper is bright yellow, the size of a double-decker bus, and it’s older than I am. (And I’m old enough that if I’d given it the old school try in my late teens I could be a grandmother by now.) I gather it’s an ancient RAF war-horse, long since pensioned off to a life of rescuing lost yachtsmen and annoying trawler captains. It’s held together by layers of paint and about sixty thousand rivets, and it rattles the fillings loose from my teeth as it roars and claws its way southwest towards the coast somewhere north of Newcastle. I get about ten minutes’ respite when we land at a heliport, but there’s barely time to get my sense of balance back before they finish pouring eau de tomcat into the fuel tanks and it’s time to go juddering up and onwards towards the M25 and the skyscrapers beyond.

By the time the Sea King bounces to a wheezing halt on a Police helipad near Hendon, I’m vibrating with exhaustion and stress. Violin case in one hand and suitcase in the other, I clamber down from the chopper and duck-walk under its swinging blades to the Police Armed Response car at the edge of the pad. There are a pair of uniforms waiting beside it, big solid constables who loom over me with the curiously condescending deference police display towards those they’ve been assured are On Their Side but who nevertheless suffer the existential handicap of not being sworn officers of the law. “Ms. O’Brien?”

“Dr. O’Brien,” I correct him automatically. “I’ve been out of the loop for two hours. Any developments?”

“We’re to take you to the incident site, Doctor. Um.” He glances at the violin case. “Medical?”

“The other type,” I tell him as I slide into the back seat. “I need to make a call.”

They drive while my phone rings. On about the sixth attempt I get through to the switchboard. “Duty Officer. Identify yourself, please.” We do the challenge/response tap-dance. “Where are you?”

“I’m in the back of a police car, on my way through…” I look for road signs. “I’ve been out of touch since pickup at zero one twenty hours. I’ll be with you in approximately forty minutes. What do I need to know?”

Already I can feel my guts clenching in anticipation, the awful bowel-watering apprehension that I’m on another of those jobs that will end with a solo virtuoso performance, blood leaking from my fingertips to lubricate Lecter’s fretboard and summon his peculiar power.

“The Code Red has been resolved.” The DO sounds tired and emotional, and I suddenly realize that he’s not the same DO that I spoke to earlier. “We have casualties but the situation has come under control and the alert status is cancelled. You should go—”

“Casualties?” I interrupt. A sense of dread wraps itself around my shoulders. “Is Agent Howard involved?”

“I’m sorry, I can’t—” The DO pauses. “Excuse me, handing you over now.”

There’s a crackle as someone else takes the line and for a second or so the sense of dread becomes a choking certainty, then: “Dr. O’Brien, I presume? Your husband is safe.” It’s the Senior Auditor, and I feel a stab of guilt about having diverted his attention, even momentarily, from dealing with whatever he’s dealing with. “I sent him home half an hour ago. He’s physically unharmed but has had a very bad time, I’m afraid, so I’d be grateful if you’d follow him and report back to this line if there are any problems. I’m mopping up and will be handing over to Gerry Lockhart in an hour; you can report to him and join the clean-up crew tomorrow.”

“Thank you,” I say, adding I think under my breath before I hang up. “Change of destination,” I announce to the driver, then give him my home address.

“That’s a—” He pauses. “Is that one of your department’s offices?” he asks.

“I’ve been told to check up on one of our people,” I tell him, then shut my trap.

“Is it an emergency?”

“It could be.” I cross my arms and stare at the back of his neck until he hits a button and I see the blue and red reflections in the windows to either side. It’s probably—almost certainly—a misuse of authority, but they’ve already blown the annual budget by getting the RAF to haul me five hundred miles by helicopter, and if the Senior Auditor thinks that Bob needs checking up on, well…

I close my eyes and try to compose myself for whatever I’m going to find at the other end as we screech through the rainy predawn London streetscape, lurching and bouncing across road pillows and swaying through traffic-calming chicanes.

The past twelve hours have rattled me, taking me very far from my stable center: hopefully Bob will be all right and we can use each other for support. He tends to bounce back, bless him, almost as if he’s too dim to see the horrors clearly. (I used to think he’s one of life’s innocents, although there have been times recently, especially since the business in Brookwood Cemetery a year ago, when I’ve been pretty sure he’s hiding nightmares from me. Certainly Gerry and Angleton have begun to take a keen interest in his professional development, and he’s started running high-level errands for External Assets. This latest business with the PHANGs—Photogolic Hemophagic Anagathic Neurotropic Guys, that’s bureaucratese for “vampire” to me or thee—has certainly demonstrated a growing talent for shit-stirring on his part. Almost as if he’s finally showing signs of growing up.) I keep my eyes closed, and systematically dismiss the worries, counting them off my list one by one and consigning them to my mental rubbish bin. It’s a little ritual I use from time to time when things are piling up and threatening to overwhelm me: usually it works brilliantly.

The car slows, turns, slows further, and comes to a halt. I open my eyes to see a familiar street in the predawn gloom. “Miss?” It’s the driver. “Would you mind signing here, here, and here?”

A clipboard is thrust under my nose. The London Met are probably the most expensive taxi firm in the city; they’re definitely the most rule-bound and paperwork-ridden. I sign off on the ride, then find the door handle doesn’t work. “Let me out, please?” I ask.

“Certainly, miss.” There’s a click as the door springs open. “Have a good day!”

“You too,” I say, then park my violin and suitcase on the front door step while I fumble with my keys.

Bob and I live in an inter-war London semi which, frankly, we couldn’t afford to rent or buy—but it’s owned by the Crown Estates, and we qualify as essential personnel and get it for a peppercorn rent in return for providing periodic out-of-hours cover. Because it’s an official safe house it’s also kitted out with various security systems and occult wards—protective circuits configured to repel most magical manifestations. I’m exhausted from a sleepless night, the alarms and wards are all showing green for safety, the Code Red has been cancelled, and I’m not expecting trouble. That’s the only excuse I can offer for what happens next.

The key turns in the lock, and I pick up my violin case with my left hand as I push the door open with my right. The door swings ajar, opening onto the darkness of our front hall. The living room door opens to my right, which is likewise open and dark. “Hi honey, I’m home!” I call as I pull the key out of the lock, hold the door open with my left foot, and swing my suitcase over the threshold with my right hand.

I set my right foot forward as Bob calls from upstairs: “Hi? I’m up here.”

Then something pale moves in the living room doorway.

I drop my suitcase and keys and raise my right hand. My left index finger clenches on a protruding button on the inside of the handle of my violin case—a motion I’ve practiced until it’s pure autonomic reflex. I do not normally open Lecter’s case using the quick-release button, because it’s held in place with powerful springs and reassembling it after I push the button is a fiddly nuisance: but if I need it I need it badly. When I squeeze the button, the front and back of the case eject, leaving me holding a handle at one end of a frame that grips the violin by the c-ribs. The frame is hinged, and the other end holds the bow by a clip. With my right hand, I grasp the scroll and raise the violin to my shoulder, then I let go of the handle, reach around, and take the fiddle. The violin is ready and eager and I feel a thrill of power rush through my fingertips as I bring the instrument to bear on the doorway to the living room and draw back a quavering, screeching, utterly non-euphonious note of challenge.

All of which takes a lot longer to write—or to read—than to do; I can release and raise my instrument in the time it takes you to draw and aim a pistol. And I’m trained for this. No, seriously. My instrument kills demons. And there’s one in my sights right now, sprawled halfway through the living room doorway, bone-thin arms raised towards me and fangs bared.

***Yesss!!!*** Lecter snarls triumphantly as I draw back the bow and channel my attention into the sigil carved on the osseous scrollwork at the top of his neck. My fingertips burn as if I’ve rubbed chili oil into them, and the strings fluoresce, glowing first green, then shining blue as I strike up a note, and another note, and begin to search for the right chord to draw the soul out through the ears and eyes of the half-dressed blonde bitch baring her oversized canines at me.

She’s young and sharp-featured and hungry for blood, filled with an appetite that suggests a natural chord in the key of Lecter—oh yes, he knows what to do with her—with Mhari, that’s her name, isn’t it? Bob’s bunny-boiler ex from hell, long since banished, latterly returned triumphant to the organization with an MBA and a little coterie of blood-sucking merchant banker IT minions.

I put it all together in a single instant, and it’s enough to make my skull pop with rage even as my heart freezes over. Code Red, Bob damaged, and I get home to find this manipulative bitch in my home, half-dressed—bare feet, black mini-dress, disheveled as if she’s just don’t go there—I adjust my grip, tense my fingers, summoning up the killing rage as I prepare to let Lecter off his leash.

“Stand down!”

It’s Bob. As I stare at Mhari I experience a strange shift in perspective, as if I’m staring at a Rubin vase: the meaning of what I’m seeing inverts. She crouches before me on her knees, looking up at me like a puppy that’s just shit its owner’s bed and doesn’t know what to do. Her face is a snarl—no, a smile—of terror. I’m older than she is, and since becoming a PHANG she looks younger than her years, barely out of her teens: she’s baring her teeth ingratiatingly, the way pretty girls are trained to. As if you can talk your way out of any situation, however bad, with a pretty smile and a simper.

The wards are intact. Bob must have invited her in.

I am so stricken by the implicit betrayal that I stand frozen, pointing Lecter at her like a dummy until Bob throws himself across my line of fire. He’s wearing his threadbare dressing gown and his hair is tousled. He gasps out nonsense phrases that don’t signify anything: “We had an internal threat! I told her she could stay here! The threat situation was resolved about three hours ago at the New Annex! She’s about to leave.”

“It’s true,” she whines, panic driving her words at me: “there was an elder inside the Laundry—he was sending a vampire hunter to murder all the PHANGs—Bob said he must have access to the personnel records—this would be the last place a vampire hunter would look for me—I’ve been sleeping in the living room—I’ll just get my stuff and be going—”

She’s contemptible. But there’s someone else here, isn’t there? I make eye contact with Bob. “Is. This. True?” Did you really bring her back here? Is this really what it looks like?

Bob seems to make his mind up about something. “Yes,” he says crisply.

I stare at him, trying to understand what’s happened. The bitch scrambles backwards, into the living room and out of sight: I ignore her. She’s a vampire and she could be gearing up to re-plumb my jugular for all I know, but I find that I simply don’t give a fuck. The enormity of Bob’s betrayal is a Berlin Wall between us, standing like a vast slab of irrefrangible concrete, impossible to bridge.

“You didn’t email,” I tell him. Why didn’t you email?

“I thought you were on a—” His eyes track towards the living room door. Every momentary saccade is like a coil of barbed wire tightening around my heart. “Out of contact.”

“That’s not the point,” I say. “You invited that—thing—into our house.” I gesture, carelessly swinging Lecter to bear on the living room doorway. The vampire whimpers quietly. Good.

“She’s a member of non-operational staff who has contracted an unfortunate but controllable medical condition, Mo. We have a duty to look after our own.”

His hypocrisy is breathtaking. “Yes well, I can see exactly how important that is to you.” The thing in the living room is moving around, doing something. I lean around the doorway. “You,” I call.

***It can’t hear you,*** Lecter tells me. ***You can only get her attention in one way. Allow me?***

I rest the bow lightly across the bridge and tweak gently, between two fingers. Lecter obliges, singing a soul into torment. “Keep away from him, you bitch,” I call through the doorway.

The vampire moans.

“Stop hurting her,” someone is saying.

I keep moving the bow. It’s not something I can control: the notes want to flow.

“Stop!” Bob sounds upset.

“I can’t—” The bow drags my fingers along behind it, burning them. I’m bleeding. The strings are glowing and the vampire is screaming in pain.

I try to lock my wrist in place but the bow is fighting me. I try to open my fingers, to drop the bow. “It won’t let me!”

***You want me to do this,*** Lecter assures me. His voice is an echo of my father (dead for many years), kindly, avuncular, controlling. ***This is simply what you want.***

“Stop,” says Bob, in a tongue and a voice I have never felt from him before. He grabs my right elbow and pinches hard: pain stabs up my arm. There’s a rattling crash from the living room as the Vampire Bitch from Human Resources legs it through the bay window and runs screaming into the predawn light.

***Mistress, you will obey,*** hisses Lecter, and there’s a cramp in my side as he forces me to turn, raising his body and bringing it to bear on my husband in a moment of horror—

“Stop,” Bob repeats. He’s speaking Old Enochian; not a language I thought he was fluent in. There’s something very weird and unpleasantly familiar about his accent.

I shake my head. “You’re hurting me.”

“I’m sorry.” He loosens his grip on my elbow but doesn’t let go. Something inside me feels broken.

“Did you have sex with her?” I have to ask, God help me.

“No.”

I drop the bow. My fingers tingle and throb and don’t want to work properly. They feel wet. I’m bleeding. I finally manage to unkink my elbow and put down the violin. Blood is trickling along its neck, threatening to stain the scrimshaw.

“You’re bleeding.” Bob sounds shocked. “Let me get you a towel.”

He vanishes up the hall corridor and I manage to bend down and lay the violin on top of its case. I don’t trust myself to think, or to speak, or to feel. I’m numb. Is he telling the truth? He denies it. But is he? Isn’t he? My ward should tell me, but right now it’s mute.

A sharp realization hits me: regardless of what Bob may or may not have been up to, Lecter wants me to think the worst of him.

Bob hands me a roll of kitchen towels, and I tear a bunch off and wrap them around my hand. “Kitchen,” I say faintly. I don’t trust myself to speak in any sentence longer than a single word.

We get to the kitchen. I sit down quietly, holding the bleeding wedge of tissue to my fingertips. I look around. It seems so normal, doesn’t it? Not like a disaster scene. Bob just hangs around with a stupid, stunned expression on his face.

“She’s a vampire,” I say numbly.

“So is that.” He nods in the direction of the hall door, pointing at Lecter and his quick-release carapace.

“That’s… different.” I don’t know why I should feel defensive. Lecter wanted to kill Bob, didn’t he? First he wanted to kill Mhari, then… Bob.

“The difference is, now it wants me dead.” Bob looks at me. He’s tired, and care-worn, and there’s something else. “You know that, don’t you?”

“When it turned on you, it was horrible.” I shudder. I can’t seem to stop shaking. The paranoia, the suspicion: they say there’s no smoke without fire, but what if an enemy is laying a smoke screen to justify terrible acts? “Oh God, that was awful.” You should be dead, Bob, something whispers at the back of my mind. Lecter is too powerful. “Bob, how did you stop it? You shouldn’t have been able to…”

“Angleton’s dead.”

“What?”

“The Code Red last night. The intruder was a, an ancient PHANG. He killed Angleton.”

“Oh my God. Oh my God.”

I lose the plot completely for a few seconds. Stupid me. I reach for him across the infinite gulf of the kitchen table and he’s still there, only different. He takes my hand. “You’re him now.” Angleton is another of our ancient monsters, the mortal vessel of the Eater of Souls. One of the night haunts upon whose shoulders the Laundry rests. For years he’s used Bob as a footstool, dropping tidbits of lore in front of him, sharing abilities, but over these past two years, Bob’s become something more: the ritual at Brookwood, where the Brotherhood of the Black Pharaoh tried to sacrifice him, changed something in him. But this is different. The way he managed to break through Lecter’s siren song…

“Not really,” he demurs. I feel a flicker of sullen resentment: his talent for self-deprecation borders on willful blindness. “But I have access to a lot of, of—” He falls silent. “Stuff.”

Unpalatable facts:

Bob and I have come this far together by treating life as a three-legged race, relying on one another to keep us sane when we simply can’t face up to what we’re doing anymore. I’ve come to count on our relationship working like this, but in the space of a couple of hours the rug has been pulled from under my feet.

This is a new and unfamiliar Bob. Whether he’s lying or not, whether he was hosting an innocent sleepover in a safe house or carrying on an affair in my own bed while I was away, pales into insignificance compared to the unwelcome realization that he isn’t just Bob anymore, but Bob with eldritch necromantic strings attached. He’s finally stepped across a threshold I passed long ago, realized that he has responsibilities larger than his own life. And it means we’re into terra incognita.

“What are you going to do?” I ask him.

“I should destroy that thing.” His expression as he looks at the hall doorway is venomous, but I can tell from the set of his shoulders that he knows how futile the suggestion is. I feel a pang of mild resentment. I’d like to be rid of the violin, too; what does he think carrying it does to me?

“They won’t let you. The organization needs it. It’s all I can do to keep squashing the proposals to make more of them.”

“Yes, but if I don’t it’s going to try and kill me again,” he points out.

I try to plot a way out of the inexorable logic of the cleft stick we find ourselves in. Of course, there isn’t one. “I can’t let go of it.” I chew my lip. “If I let go of it—return it to Supplies, convince them I can’t carry it anymore—they’ll just give it to someone else. Someone inexperienced. It was inactive for years before they gave it to me. Starving and in hibernation. It’s awake now. And the stars are right.”

This is why I have to keep calm and carry Lecter. Until someone better qualified comes along, I’m where the buck stops. And the chances of someone coming along who is more able than I—an agent with eight years’ experience of holding my course and not being swayed by the blandishments of the bone violin—are slim. I hope Bob can understand this. It’s not really any different from the Eater of Souls thing: now that Angleton’s gone, Bob’s next in the firing line.

“What are we going to do? It wants me dead,” he says dolefully.

I talk myself through to the bitter end, as much for my own benefit as for his. “If I let go of it a lot of other people will die, Bob. I’m the only thing holding it back. Do you want that? Do you really want to take responsibility for letting it off the leash with an inexperienced handler?”

I meet his gaze. My heart breaks as he says the inevitable words.

“I’m going to have to move out.”

Excerpted from The Annihilation Score © Charles Stross, 2015